T. Eliott Mansa, For Those Gathered in the Wind

Dec 2, 2020 – Feb 27, 2021

INSTALLATION VIEWS & SELECTED WORKS

“Haint” Blue

Indigo, the long green plant from the legume family, originally used to make the color blue, traces its roots to India but through the African slave trade became immensely valuable in Africa. More powerful than the gun, indigo was used as a form of currency, exchanging one length of cloth for a human body. Enslaved Africans brought their knowledge of indigo cultivation to the United States, and during the 1700s, the profits from indigo surpassed those of sugar and cotton. The importation of enslaved Africans escalated in the Southern Colonies as a result of the demand for Indigo in the mid-18th century. With that demand came a growing dependence on enslaved labor, and led to the legalization of slavery in Georgia to keep the industry thriving. After the Revolutionary War, indigo, once the main export in South Carolina, was replaced by rice and cotton.

Indigo dye and the symbolic use of the color blue for protection are deeply rooted in West African spiritual traditions. “Haint” is an old Southern word for a ghost or evil spirit from the Carolina coastal region. Enslaved Africans on the low country plantations of South Carolina believed blue would protect them and their descendants, the Gullah Geechee, from “haints” and “boo hags” — dangerous evil spirits that bring harm by slipping into your home while you are sleeping. The color was said to trick haints into believing that they’ve stumbled into water, which they cannot cross, or the sky, which will lead them farther from their intended victims.

Now more of a concept than a particular color, “Haint Blue” ranges from light or “sky” blue to periwinkle, as well as various shades of blue-green. It can be seen all over the world and is still prevalent in the southern United States, particularly in South Carolina and coastal Georgia, as well as the Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa on window shutters, doors, and porch ceilings.

Donnamarie Baptiste, Curator of “For Those Gathered in the Wind”

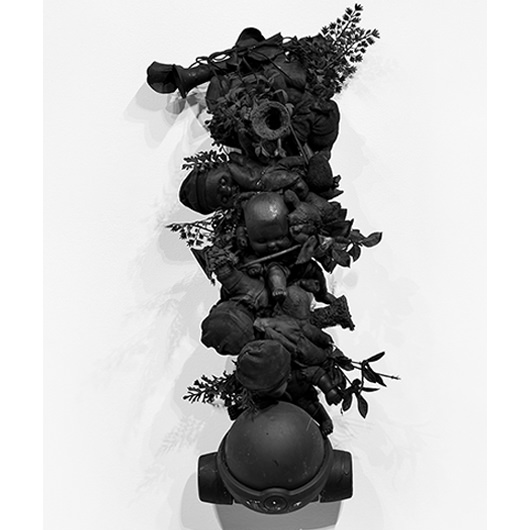

Marching and Singing with Yesterday’s Coffin on Their Heads V, 2020

toys, stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, toy guns, baby dolls, nails, and acrylic on wood 43 x 45 x 18 inches

Marching and Singing with Yesterday’s Coffin on their Heads IV, 2020

toys, stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, toy guns, baby dolls, bells, shells, and acrylic on wood 46 x 36 x 18

Marching and Singing with Yesterday’s Coffin on Their Heads VII, 2020

toys, stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, nails, toy guns, baby dolls, shells, and acrylic on wood 48 x 40 x 18 inches

For Those Gathered in the Wind V, 2019

stuffed animals, bells, locks, plastic flowers, pebbles, and acrylic on wood 14 x 11 x 7 inches

For Those Gathered in the Wind XII, 2019

stuffed animals, plastic flowers, pebbles, toy car, and acrylic on wood 19 ½ x 16 ½ x 9 inches

For Those Gathered in the Wind VI, 2019

stuffed animals, plastic flowers, toy cars, nails, belts, and acrylic on wood 12 x 14 x 6 ½ inches

For Those Gathered in the Wind XIV, 2019

stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, plastic toys, pebbles, and acrylic on wood 16 ½ x 14 x 6 ½ inches

For Those Gathered in the Wind VII, 2019

stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, beads, pebbles, toy cars, and acrylic on wood 23 ½ x 12 x 7 inches

Victory of John Henry, 2020

toys, stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, toy railroad tracks, alligator head, and acrylic on wood 70 x 49 x 12 inches

Detail: Victory of John Henry, 2020

Elegies Clustered in The Waves of The Wake V, 2020

toys, stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, toy guns, baby dolls, and acrylic on wood 60 x 54 x 20 inches

Elegies Clustered in The Waves of The Wake II, 2020

toys, stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, baby dolls, and acrylic on wood 62 x 46 x 20 inches

Elegies Clustered in The Waves of The Wake I, 2020

toys, stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, toy guns, baby dolls, shoes and acrylic on wood 60 x 52 x 20 inches

Elegies Clustered in the Waves of the Wake IV, 2020

toys, stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, toy guns, baby dolls, nails and acrylic on wood 67 x 48 x 24 inches

Elegies Clustered in the Waves of the Wake VII, 2020

toys, stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, toy guns, baby dolls, nails and acrylic on wood 67 x 48 x 24 inches

For Those Gathered in the Wind II, 2019

toy cars, plastic flowers, plastic toys, and acrylic on wood 16 ½ x 15 ½ x 9 inches

For Those Gathered in the Wind XI, 2019

stuffed animals, plastic flowers, plastic toy, toy cars, pebbles, and acrylic on wood 12 ½ x 11 ½ x 5 inches

For Those Gathered in the Wind XV, 2019

stuffed animals, plastic flowers, toy cars, nails, belts, and acrylic on wood 12 x 14 x 6 ½ inches

For Those Gathered in the Wind XVI, 2019

stuffed animals, cloth, and acrylic on wood 22 ½ x 15 ½ x 4 inches

Blow Gabriel Blow That Trumpet, 2020

plastic toys, plastic foliage, and acrylic 26 x 12 x 8 inches

Alternate view: Blow Gabriel Blow That Trumpet, 2020

Marching and Singing with Yesterday’s Coffin on Their Heads II, 2020

toys, stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, toy guns, baby dolls, nails and acrylic on wood 42 x 34 x 22 inches

Elegies Clustered in The Waves of the Wake III, 2020

toys, stuffed animals, plastic flowers, foliage, toy guns, baby dolls, nails and acrylic on wood 62 x 52 x 20 inches

Marching and Singing with Yesterday’s Coffin on Their Heads VI, 2020

toys, stuffed animals, plastic flowers and foliage, nails, toy guns, baby dolls, and acrylic on wood 56 x 38 x 19 ½ inches

Alternate view: Marching and Singing with Yesterday’s Coffin on Their Heads VI, 2020

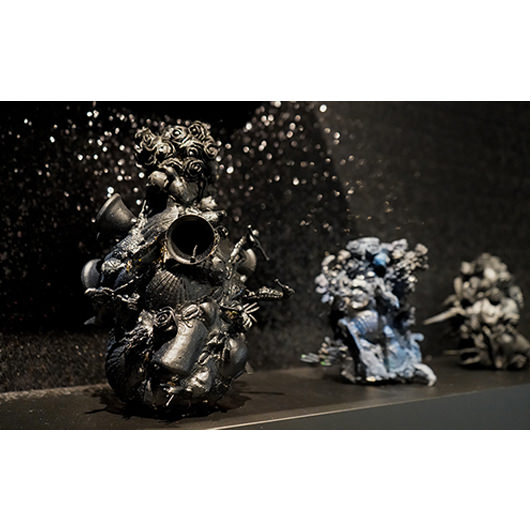

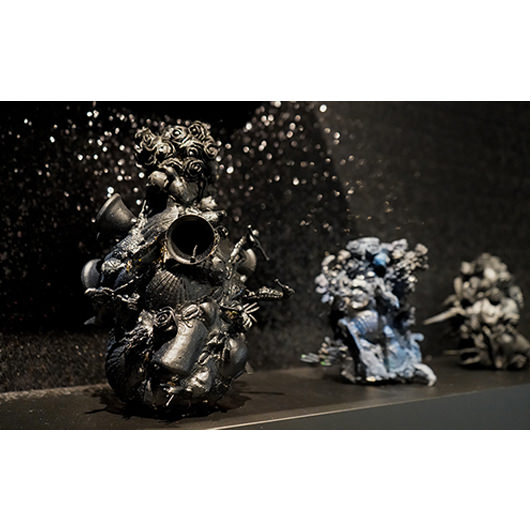

MEMORY JUGS

Enslaved Bakongo people, from what is now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola, brought the tradition of memory jugs with them to the Americas. The Bakongo people believed the spirit world was reversed and they were connected to it by water. Jugs, pitchers and vases were decorated with items from the person’s life that may be needed in the afterlife. The items were broken, as that process released its spirit so it could help the dead in their next life. They were attached with materials that include putty, cement, plaster, mortar and clay, and were placed upside down and usually kept in homes or placed gravesites. Unmarked gravesite decorations in the United States are found primarily in the South. Known by many different names, some of them include memory vessel, mourning jug, forget-me-not jug, spirit jar and ugly jar.

-Donnamarie Baptiste, Curator of, For Those Gathered in the Wind

THE BOTTLE TREE

The bottle tree reflects the historical trajectory of the transatlantic slave trade from Africa through the Caribbean to the U.S. For centuries, Kongolese captives were transplanted to the Low Country region of South Carolina and Georgia through the ports of Savannah and Charleston. African religious beliefs and traditions that survived the brutality of the Middle Passage were passed down from generation to generation, and continue to be practiced by descendants of the region, known as the Gullah, who still reside along the coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia….

Ancestors of the Gullah were some of the first people in the American South to use bottle trees. Tree branches were cut short and empty bottles were placed upside down on the shortened limbs. The enslaved believed evil spirits were drawn to the bottles by the light of the moon, and became trapped inside where they are forced to stay for the rest of the night…

Wandering spirits can be evil or those of deceased loved ones. To keep the latter from searching for things they want or need, personal items were placed at their gravesites. Objects included clocks, lamps, dishes, pots, pans, toys, etc., that were broken or punctured in some way so that the spirit of the objects could join the spirit of the deceased in the afterlife…The objects were believed to retain the power of the deceased’s spirit, while glass bottles “preserve” the abilities of the dead so they may live on.

For Those Gathered in the Wind

A solo exhibition by T. Eliott Mansa

“T. Eliott Mansa’s solo exhibition For Those Gathered in the Wind is a multi-layered conversation around Black mourning and grief in response to racism and a never-ending cycle of Black death in the United States. Simultaneously beautiful and stirring, Mansa’s assemblages merge West African traditions, the creative sensibility of Black self-taught art, and traditional roadside memorials to create new objects that have the power to protect, empower, and ease the healing process. The series was originally created as an homage to Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland,12-year-old Tamir Rice, Michael Brown and all of the unarmed Black men and women who unjustly lost their lives at the hands of police officers in the early to mid 2010s.

Taking this knowledge from the past, the artist has developed an experimental approach to sculpture making; he begins his process by gathering specific found objects including toys, shoes, plastic flowers, baby strollers, locks and more. The collected items, painted in a singular tone, seem to “become one” within the assemblages, yet each is uniquely diverse in its form and finds its own power and visual language. These assemblages invite viewers to think about how individuals express mourning.”

-Donnamarie Baptiste, Curator and essayist of For Those Gathered in the Wind